Now I would like to discuss the first of two closely linked practices. While in my lived spiritual life these two practices function harmoniously and almost inseparably, each should be treated in its own way. The first ‘technique’ (which played a huge role in my ‘newbie-Catholic euphoria’, and which I shall – and I shall! -- share here in God’s good time), I call ‘breathing with your heart’. True to form, I hereby venture yet another would-be neologism and call this first practice ‘cardiopnea’ /kar-dee‘op-nee-uh/. The second ‘technique’, which I discovered only in the last few weeks, so far has no cool name like ‘cardiopnea’, but now is as good a time as any to proffer one (or two): ‘weaving with grace’ or ‘the fireworks of grace’. But we’ll get to that in part III.

As far as breathing with the heart goes, to burst once again any illusory pretence of originality on my part, prayerful ‘breathing with your heart’ has its origins, in my mind, in two widely known prayer disciplines (and two of my favorites!): hesychasm and the Chaplet of Divine Mercy. Hesychasm, usually linked with ‘The Jesus Prayer’, is a primarily Eastern Christian method of prayer which I first encountered in college reading Henri Nouwen’s _Reaching Out_ (superb book!).

As far as breathing with the heart goes, to burst once again any illusory pretence of originality on my part, prayerful ‘breathing with your heart’ has its origins, in my mind, in two widely known prayer disciplines (and two of my favorites!): hesychasm and the Chaplet of Divine Mercy. Hesychasm, usually linked with ‘The Jesus Prayer’, is a primarily Eastern Christian method of prayer which I first encountered in college reading Henri Nouwen’s _Reaching Out_ (superb book!).  Hesychasm involves rhythmic meditative breathing and postures meant to draw the verbal and mental Jesus Prayer – ‘Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner’ – into the heart, or ‘nous’, so that it becomes an unconscious, undying prayer. Among many other places, you can learn more about this beloved practice in the Russian classic, _The Way of the Pilgrim_.

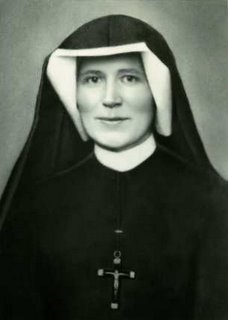

Hesychasm involves rhythmic meditative breathing and postures meant to draw the verbal and mental Jesus Prayer – ‘Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me a sinner’ – into the heart, or ‘nous’, so that it becomes an unconscious, undying prayer. Among many other places, you can learn more about this beloved practice in the Russian classic, _The Way of the Pilgrim_. As for the Chaplet of Divine Mercy, it is based on the mystical revelations Christ gave of Himself to Sr. Faustina (Helena) Kowalska, which she obediently recorded in her almost 700-page diary. Pope John Paul II had a deep love for this form of prayer, particulary since it emphasizes God’s mercy in an increasingly merciless modern world.

Using a Rosary, you begin with the basic prayers (Credo, Our Father, Hail Mary, etc.), but then on the large beads, pray, ‘Eternal Father, I offer You the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Your dearly beloved Son, our Lord, Jesus Christ.’ Then on the ten decade-beds pray, ‘For the sake of His sorrowful Passion, have mercy on us, and on the whole world.’ Finally, perhaps descending the three lowest Hail Mary beads, pray three times, ‘Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, have mercy on us and on the whole world.’ (Incidentally, the Chaplet is a great way to preserve Catholic identity without scandalizing many Protestants in an ecumenical setting... since it’s mostly ‘free’ of ‘all that Mary stuff’, donchaknow.)

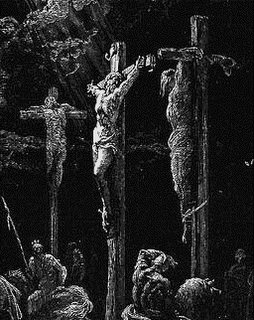

Using a Rosary, you begin with the basic prayers (Credo, Our Father, Hail Mary, etc.), but then on the large beads, pray, ‘Eternal Father, I offer You the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Your dearly beloved Son, our Lord, Jesus Christ.’ Then on the ten decade-beds pray, ‘For the sake of His sorrowful Passion, have mercy on us, and on the whole world.’ Finally, perhaps descending the three lowest Hail Mary beads, pray three times, ‘Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, have mercy on us and on the whole world.’ (Incidentally, the Chaplet is a great way to preserve Catholic identity without scandalizing many Protestants in an ecumenical setting... since it’s mostly ‘free’ of ‘all that Mary stuff’, donchaknow.) Now, the Chaplet is wonderful enough on its own; neither it nor you nor God need me to ‘enhance’ or ‘endorse’ it. But, I’m willing to say cardiopnea can enhance it – or, at least, praying with my heart enhances me. By ‘heart’ I mean, of course, my spirit, my deepest and most potent self, which is the basic biblical sense of ‘kardia’. Cardiopnea entails synchronizing my breathing with the actions, or ‘pulse’, of my heart-spirit. For example, kneeling before a crucifix, as I pray, ‘For the sake of His sorrowful Passion’, I inhale – thus literally breathing in the Crucified One! As I say, ‘have mercy on us and on the whole world’, I exhale, thus passing His crucified love from myself to others.

Obviously, this is a very imaginative process. But such vividness is, I’m convinced, vital to prayer (at least, vital to prayer before attaining the high mystical levels of ‘blindly seeing’ the ‘dark light’ of God’s ‘bitter comfort’, a la St. John of the Cross). Further, unless you’re a skeptic, cardiopnea is just as little psychological ‘trick’ as the prayer of the palms. Both are concrete, personal ways we may unite ourselves, by using *all* our selves – body, soul, imagination, intellect – to the God Who insists on meeting us in the pervasive embrace of His Holy Spirit. As I inhale, I envision Christ’s sufferings, both ‘back then’ on the Cross and now as our scarred Intercessor. Then, as I exhale, I envision any number of people – real individuals and communities, not just ‘humanity’ – and implore God’s mercy for them. In fact, I dedicate each decade to a particular ‘branch’ of people in my life: first, to my neighbors and neighborhood; next, to my family; third, to my school and co-workers; fourth, to my parish, the Pope and the Church as a whole; finally, to an especially pressing issue, which may vary from day to day. Let me be more specific still: with the words ‘have mercy on us’ I envision myself in union with a particular person (or two) and then with the words ‘and on the whole world’, I imagine the Divine Mercy spreading from that initial relational cluster to the person’s own larger relational spheres. For example, if I imagine my mom and I standing in the cloud of Divine Mercy (‘have mercy on us’), I then imagine that cloud spreading from her to other people I know she knows, say co-workers or neighbors (‘and on the whole world’).

Well, good for me, right? I should point out that cardiopnea need not, and should not, be limited to strictly devotional times. Cardiopnea is not merely a mode of intercessory prayer. It can and should be a general way of ‘processing’ life, inside and outside set prayer times. In fact, I first became aware of cardiopnea on the go, in the world, walking through a college campus, much as I’d run into the Jesus Prayer while reading on a bus in downtown Chicago. Despite how well I works with the Chaplet, only later did I incorporate cardiopnea into my prayer times. Now, when I’m in the world, and when I use the grace waiting for me, I pray with my heart as a general, non-verbal existential ‘posture’. Whenever I take note of my surroundings, whether because they are pleasing or irritating, I seek to breathe them into myself. In one big, broad mystical act of affirmation, I quite literally try to inhale my surroundings – people, objects, moods, ideas – and then exhale them all back to the Father from Whom they came in the order of Providence. Depending how vividly I imagine, I may inhale one person in particular, or may take in the whole scene from my nose to beyond the horizons.

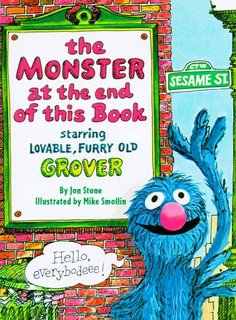

Even now, though, I sigh with frustration; for I know I am selling this practice short. I worry you may think it is only a mental inhalation, like checking off verbal items on an imagined grocery list. But it is more graphic than that, which is, I believe, crucial for its effect. The image I hope you get is that of my breath literally sucking in my surroundings, like a mighty vacuum cleaner unpeeling and lowering a tent and any other loose items into its maw. Imagine a Kansas town bracing for a twister: the tumbleweeds all, well, tumble towards the eye; drying clothes flap on the lines; buckets and rakes clatter down into the maelstrom. Or, for the less cinematic, imagine Grover's classic (for me!) book, The Monster at the End of This Book.

The book is drawn as if Grover were inside a 3-D world just behind the pages’ 2-D limits. He wallpapers and paints and hangs things in his world; meanwhile we look into it through the book, waiting for the monster to emerge on the hapless Grover. At the end of the Book, we see Grover peel away our own page to alter his own world. The two worlds interface and his actions seemingly peel ‘our’ book into his world. So it is with cardiopnea. The action of affirming Providence-as-you-find-it is a radical inhalation. The corners of perception bow in towards your heart and the only hope of purifying, redeeming and ‘eternalizing’ them is to bind them as a knot in your heart and expel them like a parcel to God for His safekeeping. Cardiopnea, then, is cathartic in the truest sense of the word.

The book is drawn as if Grover were inside a 3-D world just behind the pages’ 2-D limits. He wallpapers and paints and hangs things in his world; meanwhile we look into it through the book, waiting for the monster to emerge on the hapless Grover. At the end of the Book, we see Grover peel away our own page to alter his own world. The two worlds interface and his actions seemingly peel ‘our’ book into his world. So it is with cardiopnea. The action of affirming Providence-as-you-find-it is a radical inhalation. The corners of perception bow in towards your heart and the only hope of purifying, redeeming and ‘eternalizing’ them is to bind them as a knot in your heart and expel them like a parcel to God for His safekeeping. Cardiopnea, then, is cathartic in the truest sense of the word. By inhaling my Umwelt and the people in it, I not only affirm their goodness as gifts from God’s hands, and manifestations of His own Goodness, but also sober myself up, as it were. There is not, or at least, should not be, any dream-world spirituality. Christianity is far too ‘fleshy’, too incarnational for that. By inhaling the pollution and noise and traffic and crowdedness and anonymity – and, let’s not forget, the beauty and wonder! – of my life in Tai1zhong1, I am forced to face my self how and where I really am: humbly, feebly, here, now. Then, by exhaling my Umwelt back to the Father – by sending my dust-wrought ‘earthenness’ to His Heavenliness – I not only lift my heart’s voice in praise, but also admit I can trust my Umwelt in His hands. And, to reiterate, this is not a mere Chicken Soup for the Soul trick; it is a starkly, and sometimes, I admit, unpleasantly, sober way of facing God through the lens of His Providence, in its myriad personal and material refractions. Cardiopnea forbids escape, denial or distortion of life-as-you-find-it (which is to say the only life you have here). By breathing in even the noxious fumes of your life, you insist on integrating them into yourself, of making them a part of you, all in the good hope that God can and will redeem them when you release them to Him (from, bingo! your palms at Mass!). The more haltingly and dryly you inhale, the greater your act of faith is. The deeper you inhale – the farther back you peel the Umwelt – the deeper your love is for what God has brought you to. And why love it? Because God does too. God loves what He’s created enough to introduce you to it; breathing it in is, then, a way to breathe Him in as well.

Finally, let me mention how this practice has deepened my reflections on the Gospels. I’ll ‘out’ my ‘source’ once again here, and proudly: reflecting ‘cardiopnically’ on the Gospels is indebted heavily to my dear St. Ignatius of Loyola. On one level (or, to strain the analogy to near-bursting, in one valve!), as I read the Gospels, I try to breathe in its images, its meanings, its mysteries and, ultimately, its wisdom. On a second, more Ignatian level, I imagine Jesus Himself living cardiopnically. I imagine Him in His encounters: Which feelings or words or looks does He breathe in deeply and warmly? Which of them does He, by contrast, breathe in dolorously, redemptively? The climax of this vision hit me with almost palpable force one day. I imagined the Crucifixion: the summit of divine and human love, melted and perfectly commingled in the crucible of suffering and faith. Seeing cardiopnea as a mystical way to love your Umwelt, and seeing Jesus’ Crucifixion as the summit of love, I linked the two in a staggering way: at the Cross, Jesus inhaled every cubic inch of Creation, bound it up within Himself by the Holy Spirit, and re-committed it to the Father, now in a purified, transformed, redeemed form. Imagine the whole universe caving in to one point like swirling water. Imagine the empty darkness it leaves behind, like a Hollywood matte painting being peeled back.

‘From the sixth hour until the ninth hour darkness came over all the land’ (Matthew 27:45). At the Cross, Jesus peeled back all illusions with His mighty breath, His mighty ‘ruach’ (Heb. ‘breath, spirit’).

‘From the sixth hour until the ninth hour darkness came over all the land’ (Matthew 27:45). At the Cross, Jesus peeled back all illusions with His mighty breath, His mighty ‘ruach’ (Heb. ‘breath, spirit’). But then. Three days later. The darkness was swallowed in an even greater light. As Christ emerged from the tomb, a tomb which appeared to swallow Him as finally as He had swallowed the world in a final gasp of crucified love – from this tomb, the Lord emerged to exhale all Creation back to the Father, from His wounds, from His pierced heart, in the power of that same Holy Ruach! For us, today, to pray with our hearts is but to meet Christ in His own death-swallowing, life-giving death and resurrection.

No comments:

Post a Comment